The Palestine Papers

What are the ‘Palestine Papers’?

The ‘Palestine papers’ refers to the cache of papers leaked to the Arabic news channel Al Jazeera, shared by them with The Guardian, and published by both during the week commencing 24 January 2011. In all 1,684 documents came into their hands, including minutes, emails, studies, briefings, draft agreements, maps and charts. There are now available on the web verbatim reports (as taken down) of the meetings that the Palestinian negotiating team had with the Israelis, as well as other private discussions, notably with the Americans. The earliest document comes from 1999, the latest from late 2010, with a particularly high concentration for 2008-09 (following from George Bush’s Annapolis initiative at the end of 2007) and there are plenty of papers pertaining to the first two years of the Obama administration.

The papers give an intriguing insight into the power dynamics of meetings and the positions of participants. They are in English, the language used by all during the negotiations. Who leaked the papers is unknown. The chief Palestinian negotiator, Saeb Erekat, would like Alastair Crooke (a former British Intelligence, MI6, officer who subsequently became the Middle East advisor to the EU high representative Javier Solana), Clayton Swisher (a former American state department official now a reporter for Al Jazeera) and a Frenchman to be interviewed. It is well known that there was discontent over the depth of the concessions made in the (Palestinian) Negotiation Support Unit (henceforth NSU, paid for by the Americans and Europeans, which provided technical and legal advice to the Palestinians). It may well be that members of that unit wanted what was going on behind the scenes to be recognised. The people who feature extensively are, on the Israeli side, Tzipi Livni, Israeli foreign minister in the Olmert government during 2008-09; on the Palestinian side Saeb Erekat and Ahmed Qurei. Others who are present are the Palestinian president Mahmoud Abbas (Abu Mazen); among Americans, Condoleezza Rice and from January 2009 Hillary Clinton, Secretary of State during the Bush and Obama Administrations respectively, George Mitchell, Obama’s Special Envoy to the Middle East, David Hale, the Assistant Secretary of State for Near Eastern Affairs, and occasionally Obama himself. Tony Blair features as the Quartet’s Special Envoy to the Middle East; but otherwise Europeans are notable by their absence – an interesting comment on the what may be thought to be the woeful lack of European initiative and inclusion in this matter.

Confronted with a mass of material and commentary which is both internally connected and also sheds light on a variety of topics considered on this site I shall proceed as follows. I shall first consider various subjects discussed in the papers, listing and considering the concessions offered by the Palestinians, following this with a discussion of two matters which make a striking impact, the Jewish Israeli desire for what I shall call an ‘ethnic state’, and the extent of the security apparatus in the West Bank. I shall then consider the different parties to the negotiations: the Americans; the Israelis; and the Palestinians, in the course of which consideration I shall also discuss what emerges pertaining to Fatah/Hamas rivalry. (This section interfaces well with the consideration of these three parties in Whither Then?). Finally I shall make some evaluative comments. This is an attempt to impose some kind of order on my dealing with these papers: it will be appreciated that the topics are interwoven in the papers such that it is impossible to fully separate things out and that they relate to a number of different pages in the present website. I have worked partly from the published papers, but also from commentary. I should be grateful to be corrected if in dealing with this plethora of material I have made any obvious mistakes.

The Papers

‘PA Gave Away the Store, Israel Still Wasn’t Interested.’

(Sub-title of an article by Richard Silverstein on the liberal Jewish American blog Tikun Olam, 23 Jan. 2011.)

-

•Settlements

The context which the Palestinians brought to the discussions was that of the Roadmap, launched by Bush in 2003 and endorsed by the Quartet (the States, the EU, the UN and Russia), which stated that, in Phase I, Palestinian violence should end, while Israel should freeze settlement expansion. Justifiably enough they felt that they had kept their side of the bargain while Israel had not. Thus the NSU briefs Abbas that the settlements issue is not a case of the Palestinians imposing preconditions, but of an Israeli obligation.(1) (Israel had immediately rejected its main obligation under the Roadmap.) In speaking with Obama (according to an email from Erekat to the NSU of June 2009) Abbas is forthright:

Are you serious about the two-state solution? If you are, I cannot comprehend that you would allow a single settlement housing unit to be built in the West Bank … You have the choice. You can take the cost free road, applying double standards, which would shoot me and other moderates in the head and make this Bin Laden’s region. Or say we are not against Israel but against Israel’s actions. If you cannot make Israel stop settlements and resume permanent status negotiations who can?(2)

‘For [David Hale], and apparently for the U.S., the Roadmap requirements are just “words”. For Erekat they are a sacred international framework that in its first phase requires the Palestinians to abandon violence in exchange for the cessation of settlement expansion. The Palestinian Authority has kept its pledge. Now, Erekat is learning, the U.S. has no intention of pressuring Israel to do the same. ... Erekat can hardly believe what he is hearing - and he explodes. ... “I simply cannot go into a process that is bound to fail. ... [The Israelis are] the occupying power. They can do anything they want. ... When BO [Barack Obama] says settlements are illegitimate in front of the whole world, Israel continues, despite this and despite all international law”.’

Ali Abunimah (of the Electronic Intifada) and Mark Perry, ‘The US role as Israel’s enabler’, Al Jazeera (26 Jan. 2011).

The negotiations continue. The Palestinians make an offer. They would cede to Israel all of the West Bank on which the settlements are built around Jerusalem save only Har Homa (a settlement built by Netanyahu during his first term as Prime Minister which obstructs the passage between Jerusalem and Bethlehem). The Palestinians even suggest that part of the East Jerusalem neighbourhood of Sheikh Jarrah (where settlers have recently planted themselves amid great controversy) could be swapped for land elsewhere.

Tzipi Livni’s photostream

Ahmed Qurei, Tzipi Livni, 27 July 2010

•The Haram Al-Sharif and Jerusalem

Moshe Milner

Tzipi Livni’s photostream

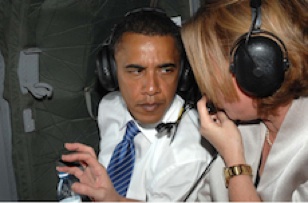

Senator Barak Obama, Israeli Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni (and defence Minister Ehud Barak) flying over the old city of Jerusalem 23 July 2008.

It is within such a context that one has to understand the significance of the suggestion made by Erekat during the talks (and the reaction to it of ordinary Palestinians). Leaning over backwards in the attempt to resolve every issue with the Israelis, he remarks to David Hale: ‘Even the Old City can be worked out except the Haram and what [Jews] call Temple Mount. There you need the creativity of people like me. …. It’s solved … there are creative ways, having a body or a committee, having undertakings for example not to dig’.(11) (The reference is to the recent Israeli ‘archaeological investigations’, tunnelling into the Haram al-Sharif, which Moslems have feared is an attempt to bring about the collapse of the Al Aqsa mosque.) The wall of the platform that is the Haram al-Sharif is of course the ‘western wall’ at the base of which Jews pray; see the photograph. How Moslems might react to Erekat’s suggestion is evident from remarks of the British Moslem leader Daud Abdullah, writing in Al Jazeera: ‘The chief Palestinian negotiator appeared totally disconnected from his own people, as well as his wider Arab and Muslim constituency, when he made this “creative” overture about Old City and the Haram. He apparently, was so consumed by the negotiations that he became oblivious of the import of his remarks among Arabs, Muslims and – most of all – his own people.’(12)

•Borders

The question of borders is of course inter-related with that of whether and if so which settlements should become part of Israel. It has been envisaged that the Palestinians should receive an equivalent amount of land elsewhere. Olmert proposed that more than 10% of the West Bank, including Ma’ale Adumim and Ariel, should be annexed by Israel in exchange for some sparsely populated farmland lying along the borders with the Gaza strip and the West Bank. A special road, unhelpfully by-passing East Jerusalem, would provide a passage between Ramallah and Bethlehem on the north/south axis. In discussion with Abbas in mid 2008, Olmert pulled out a map showing the Israeli proposed border (the red line), which map – notoriously – Abbas, when he asked to be given a copy, was not allowed to have, being reduced to making a sketch for himself on an available paper napkin. This line is now apparent through the release of the papers.

What has been highly problematic is that the Palestinians understood (for Rice assured them of this) that the starting point for discussions about borders was the 1948-67 boundary (recognised internationally by the 1948 peace agreement which created the state of Israel).(13) Thus, in conversation with Mitchell, Erekat is taken aback to find that what he thought was agreed with the Americans is, with the new American Administration, up for grabs and by no means assured. In October 2009 Mitchell tells Erekat that the United States ‘would not agree to any mention of ’67 whatsoever’ in order to avoid ‘difficulties with the Israelis’ (sic). Erekat responds, in fury: ’For God’s sake, she [Rice] said to put it on the record. It was the basis for the maps.’ The NSU subsequently prepared questions with which Abbas should politely confront the Americans. How – Abbas was to ask - did the American proposal address Palestinian interests? For it clearly prejudiced ‘contiguity, water aquifers and the viability of Palestine’.(14) The Palestinians were back to square one, unable, as Erekat had taken for granted, to build on presuppositions that he thought had been agreed with the United States.

•Refugees

For the background and general position pertaining to refugees click here.

The discussions over refugees have evidently been tense. Olmert provisionally accepted that a nominal and symbolic number of 1,000 refugees would be accepted annually for the next five years into Israel.(15) (One sometimes sees ten years suggested in the discussions, so presumably this was later changed?) Rice at one point unhelpfully mused that perhaps refugees could be resettled in South America.(16) The Israeli negotiators refused to acknowledge Israel’s responsibility for creating the problem. Some have said that it was the UN that created Israel and thus the responsibility for the refugees lies with the international community. There have been discussions about ‘suffering’, the Israelis insisting that any statement which makes mention of Palestinian suffering must also speak of Jewish suffering. To which Erekat responded: ‘But we never caused anything to the Jews. This will not be in an agreement.’(17) On the other hand, referring to Olmert’s offer, Erekat told Mitchell (Feb. 2009): ‘on refugees, the deal is there’.(18) This proposed ‘deal’ has of course infuriated refugees of the diaspora, who witness negotiators who, without consultation, claim to speak on Palestinians’ behalf, giving away their basic rights. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948) declares that those who leave their homes have the right to return to them.

The refugee question needs further to be considered in the context of the Jewish Israeli understanding of Israel as an ethnic Jewish state, considered below.

A Jewish Ethnic State?

This question - and the impossibility of resolving it - may be thought quite fundamental to the collapse of the negotiations. It underlies and affects everything else. Although it is usually considered that Israel has moved to the right under a Likud government, what is notable is that there is little apparent difference between the position of the present Israeli government and what Livni has to say in the negotiations. The Israelis want to define Israel as an ethnic Jewish state. Thus Livni to Qurei:

-

I think that we can use another session – about what it means to be a Jew and that it is more than just a religion. … Israel is the state of the Jewish people – and I would like to emphasize the meaning of ‘its people’ is the Jewish people – with Jerusalem the united and undivided capital of Israel and of the Jewish people for 3007 years.(19)

And again, to Qurei and Erekat:

-

Israel was established to become a national home for Jews from all over the world. The Jew gets the citizenship as soon as he steps in Israel, and therefore don’t say anything about the nature of Israel… The basis of the creation of the state of Israel is that it was created for the Jewish people. Your state will be the answer to all Palestinians including refugees.(20)

This of course stands in flat contradiction with what is normally taken as axiomatic in Western democratic states, that irrespective of race or religion all hold equal citizenship (as also it would appear is the case according to the Israeli Constitution). Alastair Crooke remarks: ‘Israel in this conception cannot be a multi-cultural state… Minorities claiming equal political rights within a Zionist state represent an internal contradiction, a threat to this vision of a state based on special rights for Jews.’(21)

In relation to such a proposition the Palestinian negotiators’ position has, to say the least, been ambivalent (perhaps inconsistent); moreover worryingly different for public consumption as compared with behind closed doors. When, in October 2010, Netanyahu provocatively offered that, in exchange for a freeze in settlement-building, recognition should be given to Israel as a specifically Jewish state, the Palestinian Authority turned it down, Erekat describing it as a ‘racist demand’. But, behind closed doors, comparing Israel in this respect with the Iranian and Saudi Arabian states’ self-descriptions as Islamic or Arab, Erekat can say: ‘If you want to call your state the Jewish state of Israel you can call it what you want…’.(22) Perhaps this is just a matter of terminology to him, but formal recognition of Israel as a specifically Jewish ethnic state would have untold consequences for the Palestinians. Their negotiators are well aware of this. Livni wants to suggest (in accordance with her conception of what the negotiators are about: two states, two peoples) that, as land-swaps given in exchange for land on which settlements are built, Palestinian villages on the borders with the West Bank or Gaza should become part of the Palestinian state, Israel thereby shedding itself of part of its unwanted Palestinian population. Qurei responds to her ‘This will be difficult. All Arabs in Israel will be against us.’ But another member of Livni’s team drives it home: ‘We will need to address it somehow. Divided. All Palestinian. All Israeli.’(23) There is every evidence that, for all the problems that they encounter, most Palestinian Israelis self-identify as Israelis (if Palestinian Israelis), wishing to retain their Israeli citizenship. In such a scenario the Jews would land up with 78% of the land on which Palestinians formerly lived; while a Palestinian population of roughly equal size would have a mere 28%.

Were the ethnic-state proposition to be enacted in law, the situation of the Palestinian minority in Israel, already difficult enough, would become well-nigh impossible. Responding to the leaked papers, the courageous Palestinian member of the Knesset Haneen Zoabi remarks that it is already at present the case that she can marry a British citizen and live in Nazareth, but not a Palestinian who does not hold Israeli nationality. (This is forbidden by Israel on the pretext of preventing right of return.) How much more difficult would the position of Palestinians become were they constitutionally second-class citizens. At present she can appeal to the norms of democracy. An ethnic state would ‘delegitimise’ the citizenship of Palestinians; it ‘would turn the legal, political struggle of the Palestinian national minority into an illegal and illegitimate struggle… It would become far easier to criminalise any party, individual or action that sought the establishment of genuine democracy and equality’; indeed ‘it would call into question their very future in such a state’. Further, there are repercussions in international law for a non-consensual exchange of populations. Again, it would undermine the claim of refugees to return to their homes. Himself a Palestinian refugee, Ali Abunimah comments: ‘This is an earthquake.’(25)

But the demand that Israel be recognised as a specifically Jewish ethnic state is clearly something strongly felt by many Jewish Israelis. The deputy Prime Minister Moshe Ya’lon remarks in a recent article that Israel is ‘fed up giving and giving’ [quite what?] while Palestinians refuse to recognise Israel as ‘the nation state of the Jewish people’.(26)

West Bank ‘Security’

The papers shed an extraordinary light – were it not already apparent – on the degree of co-operation between the Palestinian Authority and Israeli security. It is perhaps the most distasteful thing which comes through these documents. Security in the West Bank is seen to be micro-managed by the Israelis. The Palestinians are once again in a peculiar dilemma. Were the PA not to co-operate with Israeli security and there were to be ‘incidents’, the Palestinians would at once be castigated as ‘terrorists’. American support (not least financial support) for the PA is understood to be dependent on ‘peace’ reigning. Significantly, on meeting with the new American Administration at the White House, Abbas immediately comments that he ‘would shoulder all his commitments’ including security collaboration with Israel under (the American) Lt. General Keith Dayton.(27) Thus, by way of driving home the good behaviour of the PA to the Americans, we find Erekat telling Hale that the Palestinians had had to kill their own people to maintain law and order. A further dilemma is created by the fact that, if the PA refuses to carry out the will of the Israelis, the Israelis will act of their own accord. The following is illustrative. The Israelis say they know the address of a certain commander in the al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade (the militant Fatah organisation) and ask ‘Why don’t you kill him?’. The PA representative gives an evasive reply. A few months later, Israel kills the man concerned in a drone missile attack on his car.(28)

A peculiarly difficult aspect of this question of security is the role played by Tony Blair as the special envoy of the Quartet; as also that of the European Union (not least the British Government) in setting up and funding security on the West Bank. It seems that in 2003 (subsequent to 9/11 and the consequent American drive against ‘terrorism’) Blair, at that time the British Prime Minister, tied UK and EU security policy into a major American counter-insurgency ‘surge’ in Palestine. We learn from an article by Alastair Crooke that Bush had complained that the Europeans were not pulling their weight in the war on terror: this was Blair’s response.(29) Working in conjunction with Whitehall, in 2004 the British Intelligence service MI6 drew up a secret plan for a wide-ranging crack down on Hamas, which became a blueprint for the PA.(30) It suggested such things as the internment of leaders and activists, closure of radio stations, and the replacement of imams. The adoption of these suggestions led, for example, to the construction of prisons for the possible internment of Hamas members. Unfortunately for the West, in 2006 Hamas promptly won the elections! But according to Crooke, this simply led to an increase of ‘off-balance sheet’ assistance by the EU and the United States. Worst of all are the allegations (confirmed by human rights organisations) of torture being used by the PA security forces. Torture is apparently widely used in the Middle East; but it must be fairly embarrassing for the West when they are funding that body that it being used by PA security. It seems that, of recent years, hundreds of Hamas and other activists have been detained without trial and subjected to human rights abuses.(31) (The extent to which Fatah’s hatred of their rivals, Hamas, fuels the PA’s behaviour is something on which I comment below.)

Parties to the Negotiations

The United States

‘As an American, the reaction I draw, frankly, is one of shame. My government has consistently followed the path of least resistance and short-term political expediency, at the cost of decency, justice and our clear, long-term interests. More pointedly, the Palestine papers reveal us to have alternatively demanded and encouraged the Palestinian participants to take disproportionate risks for a negotiated settlement, and then to have refused to extend ourselves to help them achieve it, leaving them exposed and vulnerable. The Palestine papers, in my view, further document an American legacy of ignominy in Palestine.’

Robert Grenier, former Director of the CIA Counter-Terrorism Center (‘Palestine papers reveal risks for peace’, The Guardian, 24 Jan. 2011).

Wikimedia Commons

Prime Minister Ehud Olmert, Secretary of State Condoleezza Rice and President Mahmoud Abbas

What becomes apparent is the framework within which the Americans set the negotiations. Politics is the art of the possible. One never hears mentioned, as criteria, UN resolutions, or international law. Rice tells the Palestinians (who have not offered that the settlements Ma'ale Adumim and Ariel should become part of Israel): ‘You won't have a state’; no Israeli leader could accept a deal ‘without including them in an Israeli state.’(35) But if Israel is allowed to keep such settlements it is simply flouting international law. With reference to the Haram al-Sharif, Rice comments: ‘If we wait until you decide sovereignty ... your children's children will not have an agreement.’(36) Mitchell takes up the same theme, lecturing the Palestinians: ‘You have to deal with the world as it is, not as you would like it.’ He comments that there is no way for the Americans to persuade Netanyahu to freeze settlements, ‘even if we engage with the Israelis till doomsday’.(37) Things can only become worse for the Palestinians if they do not reach a settlement now.

US Department of State’s photostream

Secretary Clinton shakes hands with Palestinian Prime Minister Fayyad. Jerusalem 15 Sept. 2010

Despite this American pressure, it is by no means the case that the Palestinian negotiators have failed to be outspoken on behalf of their people. The question is how, within the present power relations and lacking American support, such outspokenness can benefit them. According to the record, Erekat tells Mitchell (in Feb. 2009) to ‘stop treating Israel as a country above the laws of man’.(38) The PA, he says, has recognized Israel (the Oslo Accords) on 78% of their former territory in exchange for a Palestinian state on the remaining 22%.

-

In exchange we have our credibility destroyed with the settlements and the wall … You have a choice. There is no need to reinvent the wheel. You have either the cost-free way: pressure us to negotiate, which means AM [Abu Mazen; viz Mahmoud Abbas] negotiating with Netanyahu under continuing settlements and without recognition – this would be the last nail in AM’s coffin, or you have another choice: take the Annapolis statement: two states and negotiations over all the core issues.(39)

But Mitchell is prepared to abandon the Roadmap; even to abandon American insistence on a settlement freeze. Erekat remarks: ‘Fair is fair. The Quartet cannot impose conditions on one side and play with “constructive ambiguity” on the other.’(40)

Whether in relation to concluding an agreement with Israel, or in emasculating Hamas, a strategy that the Palestinians (and notably Erekat) are seen to employ is to impress on the Americans that working with the PA is their only possibility. Alastair Crooke comments on Erekat and the PA ‘telling virtually every European and American they met that “Ahmadinejad is in Gaza and Lebanon”’. He continues: ‘Erekat paints the region to American interlocutors as one slipping away, as though sand through the US fingers [a favourite metaphor of Erekat’s], to Iran, Hamas, Hezbollah and al-Qaeda, with Abbas and Erekat standing as the fragile bulwark against its final takeover.’(41) In October 2009 Erekat tells Mitchell that ‘In no time you will have Azis Dweik [the Hamas speaker of the Palestinian parliament, who constitutionally assumes the role of Palestinian president when the job is vacant] as your partner’.(42) The same month, at the White House pleading with General James Jones for American support, Erekat tells him:

-

If he [Netanyahu] wants to keep Lieberman and settlement construction, then we will say to him, fine. But all you are doing is giving the region to Ahmedinejad, and to Aziz Dweik, and to Hezbollah. You will have Ahmedinejad in Gaza, in Yemen … Pakistan failed. Somalia … the Palestine question is everywhere. …

-

I am planning to go on Israeli Channel 10 to say one thing: congratulations Mr Netanyahu. You defeated President Obama. You defeated Abu Mazen. Now you have Aziz Dweik as your partner.

-

If you can’t convince Netanyahu to invest in a four-month moratorium on settlements, will anyone believe you’re going to have him agree to discuss Jerusalem, or 1967?

-

The region is slipping out of your hands like sand.(43)

It becomes evident that crushing Hamas is as crucial to Erekat as is ending Israel’s occupation. He tells the EU special representative Marc Otte that ‘reaching an agreement is a matter of survival for us. It’s the way to defeat Hamas’.(45) For her part (see below) Clinton is clear as to the American need to have the PA in place. It is a mutual symbiosis.

Israeli Jews

‘What should be taken from these documents is that Palestinian negotiators have consistently come to the table in complete seriousness and in good faith, and that we have only been met by rejection at the other end. Conventional wisdom, supported by the press, has allowed Israel to promote the idea that it has always lacked a partner at our end. If if has not been before, it should now be painfully obvious that the very opposite is true. It is the Palestinians who have lacked and who continue to lack, a serious partner for peace.’

Saeb Erekat, ‘The Palestine papers are a distraction from the real issue’, The Guardian, 26 Jan. 2011).

The Palestinian Authority

What comes across before all else is the powerlessness of the Palestinians. These are not negotiations between two teams each of which has cards to play. The Palestinians make concession after concession; which the Israelis simply mop up, say they demand yet more. (See a striking example under ‘settlements’ below.) Far from being honest brokers, the Americans are in thrall to the Israelis: when the Israelis refuse to budge (again settlements is a good example), in order that the negotiations can go forward the Americans put pressure on the Palestinians to climb down. The Palestinian negotiators are thus in a helpless position. They are dependent on the Americans (and Europeans) for the finance behind the Palestinian Authority and subject to the goodwill of the Israelis. Yet, if under pressure they give away too much, any agreement that they succeed in negotiating will be jettisoned by their own people. They will as it were stand ‘naked’ before their own people, as having collaborated but achieved nothing for their constituency. (Erekat at one point asks the Americans for a ‘figleaf’;(48) something with which he can cover himself, justifying his having attempted negotiation.) For their part the Israelis can lay down the law – and, if they wish, infinitely prolong the negotiations, which they and the Palestinians know can only be to the Palestinians disadvantage as they continue to create ‘facts on the ground’. The attempt at negotiation having ignominiously failed does, thus, seem to illustrate how right Hamas has been in their principled refusal to engage in negotiations from a position of weakness.

The immediate response of the Palestinian negotiators to these dramatic revelations was to disown them. However it is clear that the papers are no fabrication and they have in part been independently authenticated; whereupon the negotiators have changed tactic. What is of course true as former negotiator Nabil Shaath has remarked, is that ‘the question is how you read them’.(49) As I have already suggested, the documents cast a wealth of light on the invidious position in which the Palestinian negotiators were placed. The negotiators evidently knew only too well that the PA’s ability to negotiate (and indeed its continuance in power) was and is dependent on their usefulness to the Americans. They cannot conclude a satisfactory peace with the Israelis on their own. The Americans however support the Israelis, asking the Palestinians to climb down. Mitchell at one point precisely says to Erekat - the Americans having failed to bring about what was the Palestinian precondition for talks, a settlement-building freeze, the Palestinian precondition for talks: ‘The reality is no negotiations is not in your interest. So we are to come up with a statement to give you a ladder to climb down on this issue – just like you asked … Now you are arguing over the color of the ladder.’(50) Subsequent to the leak of the papers, in an article defending the position of those who had tried to negotiate on the Palestinians behalf, Erekat points out that it was agreed between the parties that ‘nothing is agreed until everything is agreed’. Pursuing this line, one might say that the Palestinians made their concessions, going as far as they possibly could. However the Israelis would not reciprocate, would not move an inch to meet them; whereupon the Palestinian offers became null and void. Further, Erekat remarks that it had always been clear that any solution agreed upon should go to a national referendum. ‘In other words, no agreement will be concluded without the approval of the Palestinian people.’(51) But if this is the case then one has to ask whether he and Abbas were so out of touch with the Palestinian people as to conceive that what they were offering to concede could have been acceptable? The evidence, for example of the second intifada, clearly suggested that this is not the case. In which case such negotiation could be of none avail.

But it also becomes evident that in the negotiations of something more sinister was afoot. I have already commented on the extent to which the PA and Fatah were using the fact that they had got on board with the Israelis and the Americans to destroy their rivals, Hamas. That suited all three parties: the Americans, the Israelis and they themselves. The negotiators, so they thought, could flaunt their loyalty and thereby win concessions. While equivocal about carrying out Israeli wishes when, at worst, it came to murdering Palestinians, it is also the case that the PA frequently took advantage of the situation, their behaviour going beyond what was decent if these negotiators were truly advocates for the Palestinian cause. They are caught – in these verbatim accounts of conversations – in the act of grovelling to the Americans and the Israelis; or sharing jokes and engaging in repartee with them, of the kind which may grow up between people who have spent many hours negotiating together behind closed doors, even if on different sides. This is fairly unedifying when made public to their own constituency, as the negotiators could never have thought would happen: it looks frankly disloyal. Insofar as they were indeed servants of their people, the tragedy is that in keeping-in with the Israelis or the Americans they were never rewarded for their compliance.

The initial reaction of the Palestinian street to the revelations came (to an outsider) as somewhat of a surprise. Far from blaming those who, behind closed doors, had been willing to give their rights away, there was a strong streak of denial that this could have been the case, protestors rather turning on Al Jazeera for these ‘fabrications’. It is perhaps a measure of how strong party loyalty is in Palestine that, in the face of what must have seemed like a vindication of the position of Hamas, Fatah supporters in Ramallah should thus stand behind their leaders. Meanwhile Hamas has unsurprisingly found it opportune to say that, as expressed by a senior Hamas official: ‘The problem now is not between Hamas and Fatah, it’s between the Palestinian people and the Palestinian negotiators’.(52) Thousands marched through Gaza, accusing Abbas of being a traitor and burning his effigy. It will be interesting to see whether Fatah can recover from the discomfort in which it has been placed. One may supposes that Erekat, in particular, has been too deeply compromised by the revelations ever again represent Palestinians. For his part Abbas is ageing and wants to resign. There may indeed be no way forward for the PA in its current form.

Evaluative Comments

cvrcak 1

Flickr Commons

Obama shakes hands with Abbas; Netanyahu looks on

2 Sept. 2010.

It is perhaps too early to say what will be the fallout from this whole sorry story. Many suggest (some with relief) that the two-state solution is now, finally, dead: shown to be bankrupt and impossible of realisation. But where do we go from here?

Nothing could have illustrated more clearly than the release of these papers that the Palestinians are in a fix. They are a nation divided between those who live in the West Bank, in Gaza, in Israel itself, and abroad in the diaspora. This is a situation which has been created by the West and which is sustained by the West. The Israelis divide and rule. In this sense the Israelis need Hamas if they are to play Hamas off before the West and before Fatah. Israel itself is becoming an increasingly ‘ethnic’ state, causing multiple problems for the minority population. The West Bank is in a stranglehold, held down by a merciless military occupation, in which an authority connives with the Israeli military to keep the Palestinian people in place. While the West does nothing effective to stop Israeli colonisation, it ‘supports’ the Palestinians by funding and advising this unelected and unrepresentative authority. Whether the dynamics of the Middle East will change radically, with Arabs who are non-compliant with Western powers coming into power, this playing into the hands of the Palestinians, it is as yet too early to tell.

It becomes apparent that the Americans and not least Obama have been decidedly naïve about chances of negotiating peace. Or else - in Obama’s case - he thought it best to bring optimism to the peace process and meanwhile to deal in generalisations and wishful thinking. Take for example his Cairo speech, in which Obama refers ambivalently to ‘continued’ settlement building, declaring it illegitimate, with no clarity as to whether existing settlements will have to go. Hamas was wary from the start, suspecting that Obama wanted ‘to go to the White House through Tel Aviv, at the expense of the Palestinians’.(53) What does seem clear is that Obama underestimated Israeli intransigence, perhaps genuinely having fallen for the belief that the Israelis put peace before land acquisition. It was as though he thought that, by throwing the whole thing open rather than following through from where the previous administration had left off, he could make a new start. But the situation of the Palestinians is not, as Obama implied in his Cairo speech, comparable to that of slaves in the States or Indians under British rule who could ultimately appeal to the democratic traditions and sense of fair play of their oppressors. Advice to Palestinians that they should get their act together, for only they can win their freedom is, in their case, quite beside the point. Even Robert Grenier (whose writing is perceptive) putting words into the mouth of Obama (were he able to do so) writes:

My message to you today is that if justice is to be won, only you can win it. Yes, you can count on the assistance of many in the international community, whose help will be substantial. But in the end, Palestinians must be the primary agents of their own liberation.

How one may ask can the Palestinians possibly be ‘agents of their own liberation’ when the Americans are supporting Israel, their tormentors, to the tune of twenty seven million dollars a day? One might well add that that party who has chosen to be ‘agents of their own liberation’, namely Hamas, have met with the riposte, when democratically elected, of being removed from power, blockaded, ostracised and starved. Again Grenier has Obama proclaim ‘You must insist upon democratic legitimacy for your leaders.’(54) Well, the Palestinians chose their leaders in a free and fair election to no avail.

The light thrown on the role the West (particularly the United States) has played is that it is shameful. The present author has been somewhat surprised to see that the Obama/Clinton/Mitchell team were doing no better and possibly worse than Rice (with Bush behind her). But it should also be remembered that the Bush Administration was dealing with Olmert and a Kadima led government, whereas Clinton and Mitchell with Netanyahu and a Likud led government. The Obama Administration has dealt in a cloud of ambivalence, throwing everything open and giving no security to the Palestinians. Erekat finds himself flabbergasted that what he thought had been agreed with Rice is no longer assured. In the face of Israeli intransigence, initial American promises give way to abject failure. It becomes apparent that the Americans (and Israelis) are working within a quite different framework, of expedience and power politics, than are the Palestinians, who suppose that the starting point is international law and prior agreements. Further, the Americans (and Tony Blair following them) seem to think that the answer lies in improving the Palestinian economy and living conditions. But that Palestinian grievances could thus be mollified is presumably mistaken. What is laid bare is that the Americans, and not least the Europeans who have put up much of the money which supports the PA, are supporting what is essentially a puppet government which, to boot, has put in place a horrific security apparatus. As far as the West is concerned it has been shown that to back an unrepresentative rump of a government, effectively of their making, is not a feasible proposition.

‘The Palestinians never extracted themselves from that structurally losing proposition especially the expectation that the Americans would deliver Israel because the Palestinians thought the were the ones being reasonable in negotiations. But it didn’t happen and it didn’t happen. The Americans constantly side with the unreasonable side and the Palestinians kept digging themselves deeper and deeper into this losing proposition.’

David Levy, a former member of the Israeli negotiating team at Taba (2001). (Quoted by Chris McGreal, ‘Reaction to the leaked Palestine papers’, The Guardian 24 Jan. 2011).

For the negotiators have clearly not simply been Quislings, thinking only to promote some private cause. (They do not come across as ‘villains’, as the left-wing Palestinian Karma Nabulsi names them). It may indeed be that their stance was unrepresentative of Palestinian opinion. But if there was any point in trying to negotiate a two-state solution, under these conditions, one has to ask how less compliant negotiators would have fared? Those who oppose negotiations can reply that even these compliant negotiators got nowhere at all; in which case the point is proved that such negotiations, under such conditions, were always pointless. But this is evident after the event, and could not perhaps have been predicted beforehand. Olmert appeared to want to bring negotiations to a conclusion, even if the conditions he offered were unacceptable. Could the pusillanimous stance of the Obama administration have been foretold? Obama offered a new start. The situation was not that simple, even if the mode of the negotiations and the siding with Israeli ‘security’ demands has been unacceptable. Such compliance appeared to be the sine qua non of talks, and the negotiators - at times only too willingly - were drawn into it. What does becomes evident is the gap between what ordinary Palestinians have been led to think is rightfully theirs and the hopes which they initially invested in the peace process, as compared with the reality of what they may finally have to accept (again under present conditions) if there is to be any settlement.

It is interesting to consider what effect the release of these papers will have on relations between Hamas and Fatah. One might think that, as the Hamas official just quoted is hoping, it will lead to a new unity among Palestinian people. But, given Palestinian tribal loyalties, the situation may well be more complex. The depths to which Fatah representatives have stooped in working with the Israel against Hamas for their own advantage would seem to make any immediate prospect of a united front unlikely. For what his opinion is worth, Alastair Crooke thinks reconciliation not possible, firstly on account of the fact that ‘the enmity towards Hamas has been so systemized, so “built-in” to every aspect of life, and to every institution, that it would require the dismantling of everything that was built by Abbas and the Americans during the last decade’.(55) But secondly because ‘there was nothing on offer. Netanyahu and Livni offered Abbas nothing. In short what is there to talk about with Hamas? Abbas has nothing to give’. He was prepared to give everything he could and got nothing in return. The conclusion is simply that the two-state solution has failed. In other words, Hamas is proved to have been right all along in its refusal to enter into negotiations with Israel from a position of weakness.

The White House’s photostream

President Barack Obama welcomes Palestinian Authority President Mahmoud Abbas to the Oval Office, May 28, 2009.

Nevertheless it is self-evident that what the Palestinians need is of course unity. Whether a different stance on the part of the surrounding Arab world, in which there are also now ‘liberation movements’, will allow this to be brought about is an interesting question. A member of the Palestinian diaspora, Karma Nebulsi envisages a national liberation movement as the only hope that the Palestinians have of achieving their aims. Citing Ho Chi Minh sitting down with the French or Nelson Mandela negotiating with the apartheid regime, she concludes that the Palestinian situation can only be ‘successfully addressed’ in the way that ‘every national liberation movement has addressed [their’s] in the past: through the unassailable strength of a popular mandate’.(61) It is indeed interesting to speculate as to whether the Palestinians could set up such a front. Can Fatah supporters, who have for so long been divided among themselves, again find the strength which the PLO knew in its early days? And, having discarded leaders who will be seen to have failed them, could such a party find a way to work with Hamas, and Hamas with them, after all the rivalry and bad blood that there has been? But furthermore the question is of course whether the Palestinians, even though they should unitedly will this, are in a position to achieve a state. Israel, with the backing of the West, has them in its grip.

What is needed is a total change of tactic on the part of the West, above all of course on the part of the Americans. The West must start from a different place: that of human rights, international law and respect for the resolutions of the United Nations (a framework which the West itself largely put in place). That is not to say that five million refugees will return to the land between the river and the sea (even if they wished to, which must seem unlikely). There will need to be some realism. But the ‘exceptionalism’ that Israel is enjoying - while we facetiously say that we require democracy in the Middle East - is intolerable. We cannot ignore the economic circumstances: that the West (above all the United States) is arming and making Israel economically viable, while Israel carries out a colonial project of the worst possible kind. What the papers show up as vividly as anything could is the farce that is afoot. The Palestinians are in an invidious position from which there is no escape; and far from helping them when they need the West’s support, that support just drains away leaving them to their lot.

Of course what would be good is that there should be free and fair elections in the West Bank in which Hamas would be happy to participate. But one must wonder how that can ever again be possible now that the populace well knows that Western aid will be withdrawn if they vote as they are not supposed to. Then alone a representative Palestinian delegation which could command the respect of their people could have talks with the Israelis, this time with the prior undertaking of the West to make sure that it should not be for Palestinians (who live on 22% of their former land) to give away any more. That would entail the end of the occupation – hook, line and sinker. Is this not the minimal that we owe the Palestinians? They have every right to think so. This is the only hope for a satisfactory two-state solution. If it cannot be reached then there will need to be a dismantling of the Israeli state as an ethnic entity and the enforcement of a one-state solution with equal rights for all, which need not exclude the possibility of built-in safeguards for each community. The point is that the West can set into reverse gear the evil which, through its lack of will-power, economic policies and political alignment, it has allowed to be perpetrated. Whether the changing situation in the Islamic world will force its hand in this is an interesting proposition. Perhaps we needed these papers to make apparent once and for all the scandal that at present pertains.

Footnotes

(1) Quoted by Ian Black and Seumus Milne ‘Barack Obama lifts then crushes Palestinian peace hopes’, The Guardian 24 Jan. 2011.

(2) Gregg Carlstrom, ‘Deep Frustrations with Obama’, Al Jazeera, 24 Jan. 2011.

(3) Quoted by Black and Milne, Guardian, 24 Jan. 2011.

(4) Carlstrom, ‘Deep Frustrations’, Al Jazeera, 24 Jan. 2011.

(5) Quoted by Black and Milne, ‘Israel spurned Palestinian offer of “Biggest Yerushalayim in history”’, The Guardian, 23 Jan. 2011.

(6) Quoted by Black and Milne, ‘Israel spurned’, The Guardian, 23 Jan. 2011.

(7) Quoted by Black and Milne, ‘Israel spurned’, The Guardian, 23 Jan. 2011.

(8) Mark Tran and agencies, ‘Barack Obama: I will not waste a minute in brokering Middle East peace’, The Guardian 23 July 2008.

(9) Quoted by Harriet Sherwood ‘Palestine papers provoke anger on streets of West Bank and Gaza’, The Guardian 24 Jan. 2011.

(10) Quoted by Daud Abdullah, ‘”Shocking revelations” on Jerusalem’, Al Jazeera, 23 Jan. 2011.

(11) Quoted by Black and Milne, ‘Israel spurned’, The Guardian, 23 Jan. 2011.

(12) ‘”Shocking Revelations”’, The Guardian, 23 Jan. 2011.

(13) Carlstrom, ‘Deep Frustrations’, 24 Jan. 2011.

(14) Gregg Carlstrom, ‘The “napkin map” revealed, Al Jazeera, 23 Jan. 2011.

(15) Quoted by Ian Black and Seumas Milne, ‘Papers reveal how Palestinian leaders gave up fight over refugees’, The Guardian, 24 Jan. 2011

(16) Quoted by Black and Milne, ‘Papers reveal’, The Guardian, 24 Jan. 2011.

(17) Laila Al-Arian, ‘”We can’t refer”’, Al Jazeera, 24 Jan. 2011.

(18) The Palestine papers: ‘I’m sick of your promises’, The Guardian, 24 Jan. 2011

(19) Quoted by Alistair Crooke, ‘Misunderstanding Israeli motives’, Al Jazeera, 24 Jan. 2011.

(20) Quoted by Crooke ‘Misunderstanding’, Al Jazeera, 24 Jan. 2011.

(21) Alistair Crooke, ‘Misunderstanding’, Al Jazeera, 24 Jan. 2011.

(22) Seumas Milne and Ian Black, ‘Palestinian negotiators accept Jewish state, papers reveal’, The Guardian, 24 Jan. 2011.

(23) Milne and Black ‘Palestinian negotiators’, 24 Jan. 2011.

(24) Haneen Zoabi, ‘Palestinian negotiators must not take key decisions on our behalf’, The Guardian, 31 Jan. 2011.

(25) Ali Abunimah ‘A dangerous shift on 1967 lines’, Al Jazeera, 24 Jan. 2011.

(26) Quoted by Harriet Sherwood, ‘Palestinians preventing Middle East peace deal, says Israeli deputy PM’, The Guardian 27 Jan. 2011.

(27) Quoted by Ali Abunimah, ‘US sidelined Palestinian democracy’, Al Jazeera, 26 Jan. 2011.

(28) Ian Black, ‘Israel asked PA to kill al-Aqsa commander’, The Guardian, 25 Jan. 2011. See also Adrian Blomfield ‘MI6 ‘drew up plan to crush Hamas’, The Telegraph, 25 Jan. 2011.

(29) Alistair Cooke, ‘Blair’s counter-insurgency “surge”’, Al Jazeera, 25 Jan. 2011.

(30) Ian Black and Seumus Milne, ‘Palestine papers reveal M16 drew up plan for crackdown on Hamas’, The Guardian, 25 Jan. 2011.

(31) G23

(32) Quoted by Laila Al-Arian ‘”We can’t refer”’, Al Jazeera, 24 Jan. 2011.

(33) Quoted by Seaumus Milne, ‘Palestinian leaders weak – and increasingly desperate’, The Guardian, 23 Jan. 2011.

(34) Ali Abunimah and Mark Perry, ‘The US role as Israel’s enabler’, Al Jazeera, 26 Jan. 2011.

(35) Milne ‘Palestinian Leaders’, The Guardian 23 Jan. 2011.

(36) Milne ‘Palestinian Leaders’, The Guardian 23 Jan. 2011.

(37) Ian Black, ‘Palestine papers, George Mitchell’, The Guardian, 24 Jan. 2011.

(38) Quoted by Mark Perry and Ali Abunimah, ‘Israel’s lawyer, revisited’, Al Jazeera, 24 Jan. 2011.

(39) Quoted by Perry and Abunimah, ‘Israel’s lawyer’, Al Jazeera, 24 Jan. 2011.

(40) Quoted by Perry and Abunimah, ‘Israel’s lawyer’, Al Jazeera, 24 Jan. 2011.

(41) Alastair Crooke, ‘What prospect for reconciliation?’, Al Jazeera, 26 Jan. 2011.

(42) Quoted by Seumus Milne, ‘Palestinian Leaders’, The Guardian, 23 Jan. 2011.

(43) Meeting Minutes, Gen. James Jones – Dr. Saeb Erekat, White House, October 21, 2009 (published by The Guardian, 26 Jan. 2011).

(44) Quoted by Laila Al-Arian, ‘Erekat: “I can’t stand Hamas”, Al Jazeera 25 Jan. 2011.

(45) Quoted by Ian Black, ‘Israel asked Palestinian Authority to kill al-Aqsa commander’, The Guardian, 25 Jan. 2011.

(46) Jonathan Freedland, ‘Palestine papers: Now we know. Israel had a peace partner’, The Guardian, 23 Jan. 2011.

(47) Harriet Sherwood, ‘Palestine papers provoke anger on the streets of West Bank and Gaza’, The Guardian, 24 Jan. 2011.

(48) Seamus Milne, ‘Palestinian leaders’, 23 Jan. 2011.

(49) BBC News, Middle East, 25 Jan. 2011.

(50) Black and Milne, ‘Barack Obama’, The Guardian, 24 Jan. 2011.

(51) Erekat ‘The Palestine papers are a distraction from the real issue, The Guardian, 26 Jan. 2011.

(52) Sherwood, ‘Palestine Papers’, The Guardian, 24 Jan. 2011.

(53) Tran, ‘Barack Obama’, The Guardian, 23 July 2008.

(54) Robert Grenier, ‘A letter to the Palestinian people’, Al Jazeera, 26 Jan. 2011.

(55) Alistair Crooke, ‘What Prospect’, Al Jazeera, 26 Jan. 2011.

(56) Cf. Ali Abunimah, ‘US sidelined Palestinian democracy’, Al Jazeera, 26 Jan. 2011.

(57) Quoted by Abunimah, ‘US sidelined’, Al Jazeera, 26 Jan. 2011.

(58) Cf. Seumas Milne and Ian Black ‘US threat to Palestinians: change leadership and we cut funds’, The Guardian, 24 Jan. 2011.

(59) Quoted by Abunimah, ‘US sidelined’, Al Jazeera 26 Jan. 2011.

(60) Quoted by Milne and Black, ‘US threat’, The Guardian, 24 Jan. 2011.

(61) Karma Nabulsi, ‘This seemingly endless and ugly game of the peace process is now finally over’, The Guardian, 23 Jan. 2011.

Bibliography

Clayton E Swisher The Palestine Papers (2011)

Moshe Milner

Israel IFMA’s photostream

3 Way Meeting, Sharm el Sheikh

L to R: Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, Secretary of State Hilary Clinton, Palestinian President Abu Mazen [Abu Abass], Special Envoy to the Middle East George Mitchell, Sharm El Sheikh 14 Sept. 2010