Maps and the Land

‘If someone had told the Jews who formed 10% of Palestine’s population at the turn of the last century that one day they would have a state spreading over 78% of the country with 80% of Jerusalem as its capital, they would have dismissed this as no more than a beautiful dream. If the other 90% of Palestine’s population were told that one day they would give up three-quarters of their land, after three-quarters of their population had become refugees, and that they would be forced to live in 10-18% of their homeland, perforated like a Swiss cheese by 200 illegal settlements protected by a nuclear-armed neighbour run by an infamous general [Sharon], they would have thought they were being offered a nightmare. When the nightmare became a reality, more and more Palestinians were willing, like the biblical Samson, to bring down the temple on the Israelis and themselves.’

(Marwan Bishara, Palestine/Israel: Peace or Apartheid, 2nd edn. 2002)

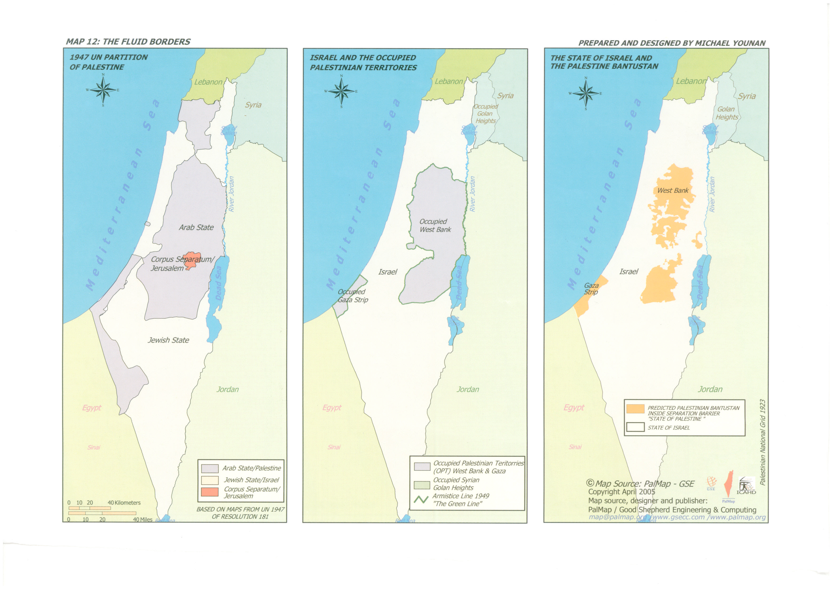

If one includes the formation of the state of Israel, land illegally occupied by Israeli settlements in the West Bank and the buffer zone of the Jordan valley which is off-limits to Palestinians, 93% of the land which was British Mandate Palestine has, since 1948, been taken from Palestinian control. So that it can evade its responsibilities under the Geneva Conventions, Israel pronounces the Palestinian territories ‘disputed’, since there has not in modern times been a legal entity ‘Palestine’. The peace treaty of 1948 creating the state of Israel gave Israel 78% of former British Mandate Palestine West of the ‘green line’, leaving the Palestinians (who were at that time part of the Jordanian state) 22%. The United Nations has declared the continued Israeli occupation of the West Bank and of East Jerusalem, land which it took in the 1967 war, illegal.

What I wish to highlight here is the way in which Israel’s conquest of the land leads one to a certain estimation as to Israeli policy. Many of those most informed about the circumstances have been brought to the conclusion that the Israelis do not actually desire peace, or their leaders do not; or one might say they only want it on their terms, such that the Palestinian people will be herded into enclaves and subjugated to Israel. If this estimate is correct then it must affect how the rest of the world approaches the question of how to bring about peace and gain justice for the Palestinians. It is going to be necessary to force such a peace on Israel (for example through economic sanctions).

The Israelis commonly say that their quest is for ‘security’. Of course this reflects the situation, insofar as the ordinary Israel does not want to be subjected to rocket attacks or suicide bombings. (Though it should be pointed out that these have largely ceased in recent years and the risk of loss of life is statistically smaller than it was for the British public during the time of the IRA offensive; see Gaza, and Hamas.) Thus the idea that it is the quest for security that underlies Israel’s offensive action first needs to be disposed of before we can move on to the question of the land.

Israel and Security

It may be that at some level Israelis feel ‘insecure’ (see A->Z, Israeli Psychology). Given the holocaust, the determination that ‘never again’ should anything of this nature pertain is handed down in the society. Israelis may see themselves as ‘David’ versus the ‘Goliath’ of the Arab world, however unrealistic this may be (see below). There is the phenomenon of what they themselves call ‘weep and shoot’ in Israeli society. It puts one in a powerful position to define oneself as the ‘victim’; other societies dare not challenge Israel for fear that they may be read as ‘anti-semitic’, in consequence applying a quite different standard to Israeli disregard of the human rights than they would in the case of say, a European country.

But in favour of the thesis that the conflict is not actually about ‘Israeli security’ the following has to be said:

-

•If the Israelis actually desired simply to enjoy peace and security they could have it on a plate. All that they need to do is to withdraw from the land that they have illegally held in a brutal military occupation for over 40 years. In 2002 the 21 countries which form the Arab League put forward a Peace Plan (the Saudi Peace Initiative) whereby Israel would be given full recognition and the conflict be over and done with in return for an Israeli withdrawal from the Occupied Palestinian Territories (the refugee question to be settled by negotiation). Even Hamas has of recent years agreed to this, saying that if a peace were to be negotiated and, in a plebiscite, accepted by the Palestinian people they would go along with this. Hamas has further offered that there should be a long-standing truce with Israel on the green line; an offer which has been repeated once and again, most recently in December 2008 when Israel chose rather to go to war. (See History & Background).

-

•Israeli military fear of the Arab world is a non-starter. Since some point in the 1960s Israel has had the upper hand: it was well recognised before the start of the ‘67 war that Israel could beat all the Arab states combined in a matter of about a week, as indeed it did. There is simply no comparison militarily. Israel is the ally of the world’s foremost superpower, supplied with $3 billion of American military aid annually, and it is widely believed to be a nuclear power. Economically Israel has an economy three times larger than those of Egypt, Palestine, Jordan, Syria and Lebanon put together and more than 40 times that of Palestine. Hamas has indeed sent rockets, but these are in large part home-made, impossible to accurately aim, and have killed few (see Gaza); besides which Israeli intelligence noted how successful was Hamas in stopping the despatch of rockets during the 6 months truce from July - December 2008. (History & Background)

The Conflict is about Land

We must conclude that the conflict is not actually about security, which Israel could have if it were so-minded. The conflict is perpetuated by the Israeli desire to expand beyond the borders that it was granted in 1948. For many right-wing Israelis this is a religious tenet; the belief that ‘God’ has given the land between the river (Jordan) and the sea to the Jews in perpetuity, what is known as Eretz Israel, including what they call ‘Judea’ and ‘Samaria’, giving that land its biblical names, which is now the West Bank. Once one starts from the recognition that the desire to conquer the land is put before any desire for peace, then Israeli policy decisions fall into place. Talk about ‘peace’ comes to be seen for what it is, a subterfuge and delaying tactic allowing quite other aims to be pursued.

An Israeli Jew living in Britain, Oren Ben Dor, writes: ‘There must be, for Israelis, some being and thinking which is preserved, indeed defended, by the pathology of provoking a permanent state of violence against [the Arabs].’ Well, the thinking is that within a state of unrest, if not out-right war, more land can be taken, or excuse found to subjugate or confine the Palestinians. As David Ben Gurion, commonly considered the ‘father’ or founder of Israel, remarked in the late 1930s: ‘What is inconceivable in normal times is possible in revolutionary times; and if at this time the opportunity is missed and what is possible in such great hours is not carried out – a whole world is lost.’ It is this which makes it opportune to have a state of continual turbulence and refuse peace.

This analysis of what is afoot is central to the analysis of the best Jewish (Israeli or non-Israeli) scholars; see for example the work of Ilan Pappé and Norman Finkelstein. The Zionist desire has from the start been to conquer the land and to drive out the indigenous population, the Palestinians. That this has been undertaken and is being undertaken stage by stage, pausing to consolidate before they move on, is simply a matter of pragmatism. 1948 is simply one stop along the road. Pursuit of this policy involves a good deal of disingenuousness, if not out-right lies. An excellent PR machine is needed so as to confuse the international community as to Israeli aims. In particular it is necessary that any attempt from the Arab side to make peace should be frustrated so that current boundaries not be set in stone.

Consider in this context the following:

-

•1948. If our thesis is correct then what happened in 1948 (which has been conveniently forgotten) is simply consistent with a wider picture, an episode in an on-going strategy. It is more especially Ilan Pappé who has brought to light what happened in 1948 together with the consequences for one’s analysis. (See the last chapter of his The Ethnic Cleansing of Palestine: the present author, unsurprisingly, found a whole heap of copies in a book shop in an Arab neighbourhood in East Jerusalem.) It is not that what was once a left-wing and kibbutz-loving country went off the rails (although it must be said that many who emigrated to Israel in the early years did have high ideals). The truth is that in 1948, in a brutal and systematic campaign (see History & Background), the Palestinian people were dispossessed. The Israeli leadership was content with the ’48 boundary simply because they could not at that stage take more. Jerusalem was not of overriding concern to a society the power base of which was in Tel Aviv.

It is interesting incidentally that the British who, during the early mandate years had enabled the first wave of immigration into Palestine, in the later mandate years became deeply worried about what they had unleashed, seeking to reign back on further Jewish emigration. By 1948 a senior civil servant (Sir John Troutbeck) was writing to Ernest Bevin, Foreign Secretary, that the Americans were responsible for the creation of a gangster state headed by ‘an utterly unscrupulous set of leaders’ (quoted by Avi Shlaim). At around the same date, by way of accounting for the ‘almost complete disregard of the Arab case’ by the Americans, the Labour politician Richard Crossman, himself a Zionist, commented: ‘Zionism after all is merely the attempt by the European Jew to build his national life on the soil of Palestine in much the same way as the American settler developed the West. So the American will give the Jewish settler in Palestine the benefit of the doubt, and regard the Arab as the aboriginal who must go down before the march of progress.’ (Quoted by Finkelstein).

•1967. Given such an analysis, the 1967 crisis takes on the guise of a god-sent opportunity. Israel precisely didn’t want peace if it was to fulfil its expansionist aims. When the Israeli leadership feared that Egypt was making peace and that the Americans might support a peace deal, they provoked war (see History & Background; for further information see Finkelstein). By 1967 Israel was ready to take land that it had not been viable to take in 1948. The opportunity which presented itself 1967 allowing Israel to grab the West Bank is widely understood in Israel as a ‘miracle’.

•Settlement Building. The fact that the major push for settlement building came precisely during the Oslo years and under a Labour Government (the time at which, if Israel was serious about making peace, this was the last thing that it should have done) is surely significant. The policy of settlement building has been a constant since. Having no intention of allowing a ‘final settlement’ to transpire, Israel has simply postponed peace-making, meanwhile consolidating what are referred to as ‘facts on the ground’.

-

•The Wall. The building of the wall inside Palestinian territory allows Israel to grab yet more land. The whole apparatus of security and control – surveillance, settler-only roads and settlements – is intended to divide up the West Bank and turn the occupation into a permanent state of affairs. The on-going demolition of Palestinian houses, whether in Israel proper or the West Bank, has the aim of pushing Palestinians out of East Jerusalem and off the land, making life unbearable for them so that they will emigrate or, if they will not do that then they must be confined in Bantustans.

-

-

• The response to Arab peace initiatives has been either to ridicule them, turning a blind eye (as in the case of the Saudi Peace initiative), or to forestall them (the ’67 war). In the face of Hamas’ offer of a renewal of the truce in December 2008, Israel once again preferred to attack. We should note further that the Israelis are never prepared to meet with Palestinians face to face (or only to meet with Palestinians whom they have under their thumb and they think compliant). Suppose a Hamas delegation were to be too reasonable? They prefer unilateral action and settling all issues by force.

-

Implications of this Thesis

If this thesis is correct then it must profoundly affect the policy of the rest of the world towards Israel. A constant state of unrest, provoking the Arab world to retaliate, has been a deliberate strategy allowing conditions to be created in which Israel could take more land. In this Israeli policy compares with German National Socialist policy during the late 1930s; one speaks peace to deceive the international community, while once and again promoting conflict in order, in the turmoil or through invasion, to be able to grab more land. Certainly the majority of the Israeli population want ‘peace’. Who wouldn’t? (We should remember that in Germany the war was deeply unpopular even in 1940 until the success of the onslaught on the West in May of that year.) But the ‘peace’ that Israel wants is that brought about by ‘pacifying’ the Palestinian people (that is to say disabling by war and occupation, or by co-optation of a compliant and self-serving Palestinian leadership). That is to say, peace on Israeli terms.

This conclusion gives the lie to the foregone conclusion that a permanent state of enmity between Arab and Jew necessarily exists, or that the conflict represents a conflict between two world-orders or outlooks. The Palestinians have repeatedly stressed that, from their perspective, the problem is not Jews per se. It is often remarked upon that, for hundreds of years, Jews lived at peace among their Moslem neighbours in Palestine. Even Hamas states that it has no problem with Jews per se, citing examples of Moslem states (as fifteenth century Spain) which displayed great tolerance towards other ‘people of the book’, as is enjoined upon Moslems. The problem is that Zionist Jews came to Palestine not to join the community but to set up their own state, dispossessing the native population. Again, the problem need not be seen as arising from some inherent Arab anti-semitism. That Arabs, in the current situation, have had a propensity to become anti-semitic is hardly surprising considering what has happened. It is rather the Israelis who have treated the Arabs as less than human and it is they - it should not be forgotten - who have the upper hand.

Those in the know whose analysis is such as I describe think what happened in the summer of 2006 in the Lebanon and the attack on Gaza in December 2008 - January 2009 only the beginning, prophesying that Israel will become ever more violent. An underlying reason for Israel’s attack on Gaza was to reestablish a sense of Israeli dominance over ‘Arabs’ subsequent to what many considered a ‘defeat’ at the hands of Hezbollah in the Lebanon in 2006. In Gaza, as also in the West Bank, Israel has shown that it will allow no hint of opposition or non-compliance with its rule. In the Israeli script as has well been said: ‘Palestinians have two “choices”: obedience or annihilation’ (Samera Esmeir). But it will not be possible to subdue in perpetuity a population through military occupation (as in the West Bank) or external control (as in the case of Gaza). In the Gaza campaign, Hamas survived a brutal onslaught. It is imperative that, before Israel takes it upon itself to act again, the international community change the balance of power through economic and cultural boycott and stopping the export of arms, making it crystal clear that as long as it fails to conform to international law Israel will be counted a pariah state.

Israel’s Forgetting

It is worth noting the deceit in which Israel has gone about consolidating its hold on the land. Ilan Pappé in particular has brought to attention how ready Israeli society has been to forget or misrepresent what happened in 1948. Pappé points to the fact that, while 1967 and the question of the occupied territories is in Israel considered a matter of legitimate discussion, what transpired in the ’48 campaign which served to create the state is a matter of taboo.

The process of forgetting (or not wanting to know) is enabled through the dissemination of myths. It has been a widespread belief in Israel that in 1948 the Palestinians ‘left of their own accord’. The truth is that they fled. A survey done (in I believe 1988) of older people who remembered the Nakba posed the question as to whether they had heard of massacres that the Jews had perpetrated in other places and indeed they had. If this is the situation in Israel, it does not compare with what has been believed in some circles in the United States. The idea has been put around, in particular by an infamous best-seller, Joan Peters’ From Time Immemorial, that the Jewish settlers found an essentially vacant land. Norman Finkelstein has shown this thesis of this book to be wholly false. Post 1948 there was in the newly formed state of Israel a deliberate effort to forget. The land where Palestinian villages had been raised were planted with trees, creating parks, so that the remains should be hidden. More recently the million-strong emigration to Israel from the former Soviet Union countries since 1989 has made the situation yet more problematic. These immigrants, largely of right-wing disposition, have scant knowledge of the history of Palestine; making comments to Palestinians as ‘where did you come from?’, or believing that the British brought them, or supposing them to be Egyptians.

The same obfuscation of the past that there has been in regard to 1948 is now taking place in relation to 1967. The path of the green line is not taught in Israeli schools. The group of Palestinian Israelis who met with their Jewish Israeli counterparts of whom we learnt on the visit in which I partook (see A->Z, Women) were astonished to find that the Jewish Israelis seemingly had no knowledge of the course of the line. Israel of course deliberately encourages this. The Ministry of Tourism has pursued a policy of deliberate obfuscation (see BDS, Israel and Tourism) and it is indeed not shown on the tourist map of Israel in the present author’s possession. An advertisement on the London tube to attract people to Israel on holiday, now banned, depicted not only the West Bank but also Gaza (which Israel is supposed to have evacuated) as part of Israel! Perhaps these maps are a good indication of how Israelis think about the land at a subconscious level.

The contrast with Palestinian society in this respect could not be starker. In that community maps are everything. A map showing the depth and breadth of the occupation is the first thing one sees, prominently displayed, when entering the library at Bethlehem University. In Ni’lin their map of the encroaching wall and barbed wire fences which divide them from their land looked to be what the village revolved around. Maps represent to Palestinians both the present horror and the hope for the future; the wager that the truth of the situation shall not be forgotten and justice will yet be done. Israelis will never be able understand, let alone converse meaningfully, with Palestinians until their responsibility for the past is both recognised and acknowledged. Not least, will it be impossible to deal with the question of the descendants of the 1948 refugees.

Israeli Strategy

Israel has employed particular strategies for conquering the land. The aim (pursued in different ways in different circumstances) has been to take as much land as possible while embracing as little Palestinian population as possible. The best would be that the Palestinians should simply leave; if they do not then they are to be contained.

In 1948 the tactic frequently pursued was to surround Palestinian villages on three sides, leaving the fourth open in the direction in which the Jews wanted the inhabitants to flee. The houses were subsequently raised to the ground, so that there was nowhere to which to return. Whereas Palestinians were encouraged to leave, if they tried to return they were summarily shot. One man whom we met when I visited, born in Jordan as a refugee, had been carried back into Palestine across the river on the shoulders of the tallest man in their group. A car-full of people who had declined to give them a lift thinking it was too dangerous to take a baby had all lost their lives. In Jaffa the fourth side left open was towards the sea; hence many fled to Gaza and to the Lebanon.

Shir Hever describes how Israeli expansion through settlements at present takes place. A group of colonists want to establish a new neighbourhood and do so right at the border of land already cleared of Palestinians surrounding an existing settlement, which may be 7 km away. The Israelis connect the new settlement to water and electricity and provide minimally a transportation road. The new settlers tell the army they don’t feel safe (so close to Arab land) and ask for help and protection. The army proceeds to kick out Palestinians, shepherds and undertake house demolitions. Thus there is another sterile area free of Palestinians in which the colonists feel safe. The settlers then say to the Ministry of the Interior that all this land is empty, so why not add this land to the municipal land of the original colony. And so the story repeats itself as another satellite is created yet further out. By this means, Hever comments, colonists can very rapidly increase their control over the land. (See Shir Hever U-tubes ‘The Political Economy of Israel’s Occupation’.)

Through their settlement policy the Israelis have created ‘facts on the ground’ which it was thought it would not be possible to undo. Ben Gurion famously remarked: ‘Let the Gentiles talk, the Jews will act’. Again, Ariel Sharon, former General and subsequently Prime Minister, was to comment: ‘grab every hilltop; what we take will remain ours’. To build on hill tops is of psychological import, telling the Palestinians in no uncertain terms who is dominant. The placing of major settlements blocks has been strategic. The vast Ma’ale Adumin settlement area, extending north-east from Jerusalem, blocks any north-south corridor so necessary to a potential Palestinian state (given that there would be two north-south states running parallel). Again, settlements are built over aquifers, the water being diverted from Palestinian to Israeli use, whether to settlers or Israel itself.

The Israeli government has often been deft in letting events take their course and then securing the results (for which the government is then not directly responsible). The taking of East Jerusalem in 1967 was largely left to groups of soldiers, who just went ahead while the authorities turned a blind eye. Subsequent to 1967, settlers have done likewise, taking the law into their own hands and subsequently being supported by the Israeli government. A group of settlers will in the first instance set up caravans on a hilltop. Then the government will send in soldiers to protect them and lay on utilities. The same happened in the inner city in Hebron, Israel subsequently protecting settlers who had gone there of their own accord. Thus the settlements expand piecemeal as well as being planned.

That gaining land is the driving concern of course makes sense of the whole saga of house demolition and making life for Palestinians so unbearable that they will leave, preferably emigrate. It is interesting that one lawyer of whom I heard (I believe Israeli and supporting Palestinians in the many legal cases that there are) commented that she has almost zero success in cases involving land. Meanwhile, given that wholesale transfer of the Palestinian population is nigh impossible though contemplated, as is also genocide, the only answer is to corral the unwanted population into Bantustans, surrounded by walls and barbed wire. (See Solutions?, Bantustans.) Given that cheap labour is now available from abroad, the Palestinian population is no longer even needed as an underclass to work in Israeli industry or on settler building sites.

Israeli Economy and the Occupation

We should not however think that the propensity to go for turmoil and war rather than negotiation and peace is simply on account of the wish to create the opportunity to take land. An article in Ha’aretz, the liberal Israeli newspaper, (11.05.09) gives a succinct account of the economic advantages accruing to Israel from the occupation. ‘Successive Israeli governments since 1993 certainly must have known what they were doing, being in no hurry to make peace with the Palestinians.’ They ‘understood that peace would involve serious damage to national interests’. The Israeli security industry is a major exporter: weapons and the whole paraphernalia of surveillance and deterrence equipment needed for population control can be tested daily in the siege of Gaza and in the protection of settlements in the West Bank. Meanwhile the maintenance of the occupation employs hundreds of thousands of Israelis: professional soldiers, foreign consultants, weapons dealers. Furthermore, any peace agreement would require equal distribution of water resources: the slash in water consumption required would be ‘traumatic’ for Israelis. The settlements, comments Ha’aretz, ‘offer ordinary people what their salaries would not allow them’ within the 1967 borders: ‘cheap land, large homes, benefits, subsidies, wide-open spaces, a view, a superior road network and quality education’. For Jews who have not moved there ‘the settlements illuminate their horizon as an option for a social and economic upgrade’. People who have become ‘used to privilege under a system based on ethnic discrimination see its abrogation as a threat to their welfare’. Reasons for maintaining the occupation are clearly manifold. Were it not for these multiple advantages the occupation would, in purely economic terms, in a ‘normal’ situation, be economically draining. (See Economy).

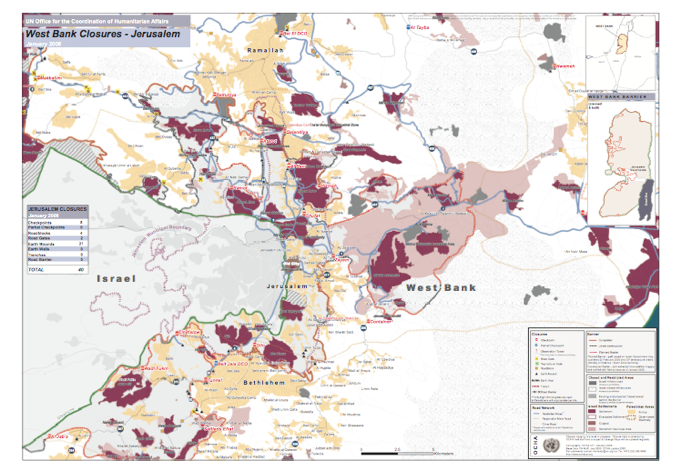

OCHA

Map showing the extent of West Bank closures in the Jerusalem Area.

Find detailed up-to-date OCHA maps click here.

Maps by Michael Younan,

Jeff Halper, Obstacles to Peace

See further on this site:

-

-BDS, Israel & Tourism